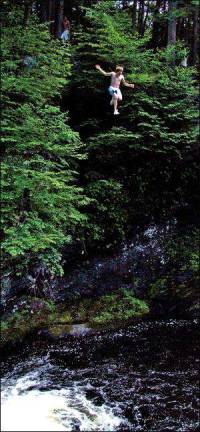

Leaping into the unknown

Story and photos by Nick Troiano Bushkill Sometimes it’s 20 feet, other times, 70. Sometimes there are cheers by friends, other times, screams of a close call. It’s all about the adrenalin, the rush of the free fall. Then, God willing, comes a splash. Cliff jumping has always been a youthful summer activity in this riverside town, but Pike County may be experiencing a rise in this dangerous trend among teens in the area. “It is like having a water park in your backyard,” said Brad, a jumper of four years. They leap from ledges of all heights, occasionally doing flips, into the water below. Some require a running start; others require a leap of faith. Currently, there are about seven different locations he and his friends visit frequently. Brad said the places where they normally jump from, such as Hackers Falls, are becoming overcrowded. He said as this activity gains popularity, teens are finding new falls and ledges to frequent. As seen in the following account, trekking deep into the wilderness adds to what many see as an already immense risk of serious injury or death. Travis, an 18-year-old resident of Milford, said he was always scared of heights, but quickly got over that once all his friends started to jump. Peer pressure, as other avid jumpers contend, is one of the major reasons the activity is becoming more popular. On one afternoon in July of last year, Travis and three of his friends wanted to find a new spot that not a lot of people, including the park rangers, would find as easily n a move that would almost cost him his life. They took what he estimates as a 1.5 mile walk through rough terrain to Adams Falls. Feeling fearless and invincible after jumping from ledges as high as 60 feet, Travis scaled straight up the waterfall. Half his body was already over the top before he ran into some trouble. “I couldn’t find any more crevices,” he said. After losing his grip, he fell and painfully tumbled backwards down the waterfall. His friends and a few bystanders retrieved him from the water while others called 911. Since Travis was unable to walk the entire way out because of his injuries, the rescue became a very arduous process. It was a half hour before a park ranger reached him and another hour before paramedics arrived. “What a poor decision I made. There was no need for it,” Travis recalls thinking to himself while waiting in the wilderness. He eventually made it to the roadside in a metal basket on U.S. Route 209 where, unbeknownst to him, traffic was blocked off in both directions and a helicopter sat waiting to medivac him to the hospital. The five-hour rescue, three months of recovery, and tens of thousands of dollars in medical bills are things he said he will never forget. Unfortunately, the memory of this traumatic event is fading from the minds of his friends, Travis said. “It just doesn’t faze them anymore. Unfortunately, it will probably take another serious accident for people to realize that bad things actually can happen,” Travis commented. Such a prospect is one of the greatest concerns of Chief Ranger Phil Selleck, of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Selleck pointed out that injuries like that of Travis are not an uncommon occurrence. In fact, just last week, a park visitor broke both his ankles after jumping from a cliff at Factory Falls. The park has also had at least three fatalities related to jumping from heights into the creeks or river. Gregg Bitondo, a 17-year-old high school student at Kittatinny Regional High School, lost his life on May 11, 1999. The honor student and football quarterback jumped from a height of 30 feet at Raymondskill Falls and landed on a rock shelf below. Two other deaths occurred within the park in Karamac, New Jersey in both 2002 and 2004. “It is a very dangerous activity happening in uncontrollable circumstances,” Selleck said. He explained that in addition to the sheer danger of jumping from such heights onto possibly concealed objects below such as rocks or logs, cliff jumpers are also threatened by the water. Selleck said in places where jumpers enter a body of water near a waterfall they face the threat of being sucked under by powerful hydraulics. He recalled once instance of a drowning near a waterfall where it took rangers nearly a full week to retrieve the body because of these hydraulics. From the Interstate Highway 80 bridge to Childs Park, cliff jumping is a daily occurrence in the park. Selleck said that rangers are beginning to crackdown on the general misuse of park lands and “cliff jumping is a significant part of that.” He said that the rangers patrol these locations as often as they can and are in the process of adding additional signage to inform visitors of this illegal activity. But over the past decade, his staff has experienced a cutback on resources. These cutbacks nearly halved the numbers of rangers, making laws like the one against jumping difficult to enforce. Currently, there are 12 rangers responsible for patrolling all 72,000 acres of the park. On the books, cliff jumping is a citable offense and carries a penalty from $75 up to $5,000 and jail time. Luc, a 16-year-old cliff jumper from Dingmans Ferry with nine years of experience under his belt, was hit with a $125 fine and had to call his parents after being caught by a park ranger. “If you ask me, it’s a little ridiculous to prevent kids from doing something that was naturally put on this planet for the taking,” he said. “Cliff jumping is no doubt a major risk, but I thrive off such a feeling.” Selleck said that young cliff jumpers should “go find a diving board” if they like to jump from heights. “It is an extreme danger the evidence is in the injuries and deaths we had so far,” he said. “Cliff jumping is also an unnecessary burden on our emergency response system,” he said. Holding its ranking as the eighth most visited national park of 391 in the country, the Delaware Water Gap is also in the top ten most dangerous. “Know your limits n that should be your motto in the park,” Selleck said. Gregg Bitondo’s parents wanted jumpers to consider others. “All we ask is for kids to step back and think before they behave in a manner which may jeopardize their safety or life ... it can alter family members’ lives forever,” said Mr. and Mrs. Bitondo.