Latest front in the culture wars: school library books

Education. Local districts take heat for books that members of the public say are “pornographic,” “divisive,” and “demonizing.”

Angry speakers called Gender Queer: A Memoir “dangerous to developing brains,” and said including the book in the S.S. Seward Institute secondary school library amounted to the “gaslighting of pornography.”

Attendees at a Florida, N.Y., school board meeting in November expressed their opposition to this illustrated coming-of-age story by nonbinary author Maia Kobabe – which includes a panel of an erotic ancient Greek vase and a depiction of oral sex. It tops a list of hundreds of books on race, colonialism, sex, and gender identity being challenged nationwide in what has become the latest front in the culture wars.

The controversy fizzled out in Orange County, N.Y. Gender Queer remains in a section of the S.S. Steward library where students have to request it. “It’s basically become a non-issue at this point,” said John Redman, the Florida school board president.

Four months later, the library book debate is just heating up in Pike County, Pa.

“Some of these books are highly, highly questionable,” said Matthew Contreras of Milford, Pa., at a Delaware Valley School District board meeting in February. “There is extreme sexual content in them.”

Contreras, a former U.S. Naval communications officer, is president of a new group called Pennsylvania Advocacy for Children’s Education. He has been a vocal presence at recent school board meetings, although he has no kids in the district. “Not knowing that they were in the district is not an excuse,” said Contreras. “An 11-year-old can walk into the library right now and pick out some of these highly explicit books on pedophilia, on sodomy, on rape, on all sorts of topics, and it’s not acceptable that the school district has not called an emergency meeting.”

Neither school district has moved to pull any books. “This is a small group of parents concerned about a small group of books right now,” said Delaware Valley Superintendent Dr. John Bell.

“Some people feel like we were just supposed to yank the book off the shelf immediately,” said Redman. “Well no, that’s not how one does it, because then you’ve got a real slippery slope.”

A slippery slope

In Sparta, N.J., the new superintendent, Matthew Beck, made a different call under similar circumstances. He quickly pulled a book about a police killing of a Black boy from seventh- and eighth-grade reading lists after parents complained in June that it was “propaganda and race baiting,” that it “perpetuates a dangerous narrative.”

Within a week of taking the helm, Beck opted to “immediately hit ‘pause’” on Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes until it could be properly vetted (though it remains in the middle school library).

“We are all aware of the type of division that has been created by these types of storylines, many of which are not told accurately portraying cops as racist and demonizing a profession which should be held in the highest regard,” wrote parent Daniella Raffo, an alum of the Sparta school system and active PTO member, in a letter to the superintendent obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. “Do I believe our children should be taught about equality and racism? Absolutely! This district does an excellent job doing that with their teachings focused on diversity and inclusion.” But, she wrote, “I would be horrified if my children came across this book in school.”

Parent Heather Donnelly submitted a similar letter. “Both of my middle school students have come home upset as kids are openly speaking poorly about police, and how police ‘suck,’ are ‘murderers,’ and should be ‘defunded,’” she wrote. “It’s hard enough nowadays being the children of police officers.”

The superintendent’s decision to remove Ghost Boys from an 11-book independent reading list – instead of simply allowing concerned parents to have their kids pick a different book – prompted an outcry from alarmed parents on the other side of the aisle. They circulated a petition to reprimand Beck and reverse the decision. In response, a three-person school board subcommittee decided that the superintendent had acted within his prerogative.

“Given that Mr. Beck was unfamiliar with the title and how it was selected, he decided that the most prudent course of action was to put the assignments on hold so that he could further look into the matter,” said a statement from the subcommittee, led by board president Kimberly Bragg. “Importantly, no student was directed to return the book while the review was being undertaken, and they were free to continue reading it on their own if they so chose.”

The school’s Supervisor of English Language Arts, Mary Hassenplug, now retired, told Superintendent Beck in a pointed email that she was “shocked that this is the response without a full discussion of the issue,” and considered his decision to pull the book without even reading it first “a statement that you do not trust your teachers or supervisors.”

“This district must have in place a system which protects the academic choices of our staff members and the learning environment for our children by leaving challenged materials in place during a review period,” said Sparta parent Kate Matteson at the November school board meeting. “It seems that the board is stating that it supports the superintendent’s suspending a resource at any time for his or her own review, as long as it is called temporary or because he is not familiar with the work,” which, she said, is in direct contradiction to the district policy.

“These policies exist to guard against government officials removing books from school curriculum simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books,” said Neill Clark, an anti-trust lawyer and step-parent of Sparta students, in a letter to the editor of this paper.

“I’m not trying to be a rabble-rouser,” said Clark. “I come from a long line of teachers. My dad taught me, ‘Look, challenge my beliefs.’ He’s a very right-wing Trump guy, I’m not. I’m used to having people I disagree with, but I think that you can disagree on amicable terms, and give me your evidence, give me your reasons, but don’t just say we’re not going to have a debate. That’s what I find problematic about what’s going on, you know?”

Melee ends in a fizzle

At the contentious November meeting of the Florida Union Free School District, librarian Vanessa Baron explained that she never suggests a book to a student, according to meeting minutes. Her responsibility is to obtain books for all races, gender identities, and ethnic groups, she said. There is a procedure, she said, for parents who have complaints about a book.

The melee ended in a fizzle: the district sent a form to a parent who’d requested it, in accordance with the process for objecting to a book, and never heard back. That was that.

As for Gender Queer, the book that caused all the stir, “it has been on the shelf for two years, and had been checked out once by a 16-to 17-year-old,” said Redman. “There was a lot of rhetoric flying around that this was accessible to 10-or 12-year-old kids, and that’s not the case. It was in a place where it would have to be requested of the librarian,” he said. It’s up to the librarian’s discretion to determine whether the book is appropriate for the student, he said. “And any books that have a certain level of controversy about them are done the same way.”

Besides, he added, “anybody, including kids, can get these kinds of books just about anywhere these days. They don’t have to depend on their school library.”

Around that time, the Florida Union Free School District instituted a policy that only district residents can speak at school board meetings. “There were people cruising around from district to district and trying to make comments, and essentially trying to disrupt things,” said Redman.

By the time Gender Queer came under scrutiny in Orange County, N.Y., it had been pulled from school library shelves from Texas to Alaska. In Virginia, Fairfax County Public Schools re-shelved the book in its high school libraries two months after its removal, when an eight-person panel unanimously voted in favor of its literary merit and value as a diverse perspective, and decided it was neither obscene nor harmful to children.

As often happens, sales of Gender Queer have skyrocketed since it became one of the most banned books in the country. The 2019 memoir is on its fifth printing with a new hardcover edition due out in June. But the author has been vocal in worrying that if it disappears from library shelves, the marginalized young people who need the book most will lose access and become further marginalized.

The book ban lists

In response to ratcheting pressure over the last month, Delaware Valley created online concern forms for parents to submit their objections to curriculum and library materials. “These forms will be used to show any common thread in the community during annual curriculum review,” wrote school board director Dawn Bukaj in a Facebook post, and “will bring concerns directly before administrators as they are received and will then be provided to the board.”

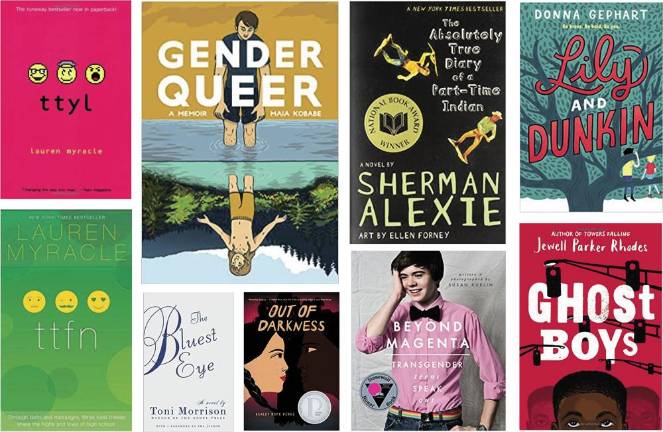

One community member – not a DV parent – had filled the form out as of Feb. 23, said Bell. She listed seven books available at the high school library: The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison; Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out by Susan Kuklin; Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez; Lily and Dunkin by Donna Gephart; The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian by Sherman Alexie; TTFN and TTYL by Lauren Myracle. Three are by non-white authors, two center on trans life, and the last two are part of the New York Times-bestselling trilogy, Internet Girls, which is heavy on sexual content and profanity.

The concerned citizen’s list was the result, said Bell, of a painstaking comparison of the district’s catalog to various watch lists circulating online, comprising well over a thousand books. “She took a great deal of time with these national lists,” said Bell. “They all get their same info from the internet.”

Groups like No Left Turn in Education and Moms for Liberty began posting lists of school library books last fall that were “indoctrinating kids to a dangerous ideology.” In October, Texas lawmaker Matt Krause compiled an 850-book list that “might make students feel discomfort,” and that went out to Texas school districts along with a letter inquiring whether they had any of the books, how many copies and where they were located, and how much money had been spent on them. More than half the titles on the so-called “Texas book ban list” are LGBTQ books.

“The interesting thing about this is the people that want unlimited free speech to talk as long as they want at a school board meeting, and want vaccines to be up to the individual, and want masks to be up to the individual, don’t want books to be up to the individual,” said Bell. “It’s all about freedom unless they don’t like something. If you’re a parent in the district, you have a say in what books your kids take out of the library. But you should not have a say in what books my kid takes out of the library. That’s the infringement on my First Amendment.”

Who reads paper books anyway?

Ironically, this laser focus on physical books comes as they are halfway down the road to obsolescence, particularly in high schools. Delaware Valley High School cut back dramatically on its physical book collection when they renovated the library four or five years ago, said Bell. The library gave away or recycled any books that hadn’t been checked out in five years to make room for a bank of 35 computers, because teens like to do their research online. Even if a high schooler wanted to do something so quaint as to check out a book, the way schedules are built now, there’s not a single free period in the week. Unless they come in early, there is practically no time to run down to the library.

In elementary school, kids visit the library weekly with their class, and can go on their own between times. “It’s a high priority,” said Bell. “Not every kid loves to read, but it forces kids to read, and then hopefully they’ll find things they like.” That priority cedes to others as kids move up. “When you get to middle school, the amount of work you have in your classes kind of consumes you,” he said. “Between work and sports and drama and stuff, kids are busy. So middle and high school kids don’t go to the library much.”

The sole exception to the downward trend in teen reading in recent memory? The Harry Potter phenomenon. “We couldn’t get enough copies of the Harry Potter books into the library,” said Bell, who was a principal at the time. “We were so excited that kids were so excited to read books. I can remember them going to Walmart at midnight to get books, middle school kids, and that was like a dream come true.”

A burden on school districts

Redman, of the Florida Union Free School District, who’s served on the school board for over 20 years, said the whole situation is just very volatile after two years pandemic stress. “People are more on edge,” he said. “I can understand that. But yes, my job as president is much more stressful than it was a year ago, just trying to maintain control of meetings without making it look like we’re being horrible to people, because we’re really trying to be as fair as we possibly can.”

In three decades as a teacher and administrator, Bell has never seen this kind of head-butting. “Everybody has an opinion about everything, and everybody is convinced they’re 100 percent right,” he said. “Every month there’s these hot topics on the internet that they’re trying to engage parents in, and library books is the latest thing on that list. But we’ve got to do our due diligence, though, and look into things, whether it’s curriculum, whether it’s textbooks.”

Though the exchanges with the public primarily take place at school board meetings, the legwork bleeds over into other work duties. “This has taken time from our librarians, and me to talk to you about it and deal with parent emails,” said Bell. “It’s time off the main task of academics.”

The latest hot topic? “People were demanding copies of our surety bonds: that every board member, every administrator is supposed to have a surety bond, and if they’re not doing what we want them to do we’re going to report them to the insurance company and get your surety bond revoked. This is stuff on the internet,” said Bell with a chuckle. “First of all, it doesn’t apply to board members and administrators in Pennsylvania. It might in other states. But people just read this stuff on the internet and drink it up. The lady was in here screaming about a surety bond. I’m like, lady, I’ve been in the business 30 years, I don’t even know what you’re talking about.”

This bizarre scheme – making pseudo-legal threats centered on obscure financial bonds – was dreamed up by QAnon adherent Miki Klann of Arizona, who started a group called “Bonds for the Win.” The claims are baseless, but across the country the tactic has been effective in intimidating, harassing, confusing, and overwhelming districts with paperwork, reported NBC on Feb. 21.

Getting through this rocky patch

Is there a silver lining to this heightened level of parental involvement in their kids’ education? Possibly.

“If we can get parents to focus on helping kids be successful, whether it’s helping them with their homework, making sure there’s a quiet place for them, stuff like that,” said Bell. “We don’t want parents that are disengaged, you know. If somehow we get through this rocky patch we’re in, and people just get more involved in their kids’ education and supporting their kids, it’ll be worth it in the end. But we’ve got to get through this rough patch where people are just criticizing everything based on something they read on the internet.”

Library books are on the agenda at the next Delaware Valley School District board meeting on March 17. Tamsen Culver, a parent of an eighth and ninth grader in Dingmans Ferry, is part of a group of parents organizing a “read-in” at 5 p.m., an hour before the school board meeting, outside the Delaware Valley High School library. The plan, she said, is for people to read aloud from a book that is being challenged as school board members and the public filter into the meeting (dvfreedomtoread@gmail.com for more info).

“The books on the list are disproportionately stories that highlight race or an LGBTQ+ character, and kids of color and LGBTQ+ students in our district deserve to see themselves represented in literature,” said Culver. “These bans are a weak disguise for racist and homophobic beliefs.”

“The people that want unlimited free speech to talk as long as they want at a school board meeting, and want vaccines to be up to the individual, and want masks to be up to the individual, don’t want books to be up to the individual,. It’s all about freedom unless they don’t like something. If you’re a parent in the district, you have a say in what books your kids take out of the library. But you should not have a say in what books my kid takes out of the library. That’s the infringement on my First Amendment.” DV Superintendent Dr. John Bell