Covid and opioids make ‘a great storm of the worst possible things’

Addiction. Overdoses increased by double digits during the first year of the pandemic in Sussex, Orange, and Pike counties, and by 8 percent in Passaic County. The disruptions and isolation of the pandemic are driving an ever-growing number of people to seek comfort in drugs while an “alarming” increase in fentanyl floods the black market.

Covid has amplified the already aggravated, ongoing opioid crisis. During the first pandemic year, 2020, the tristate area saw double-digit increases in overdoses, driven by “an alarming increase in the lethality and availability of fake prescription pills containing fentanyl and methamphetamine,” according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency’s first Public Safety Alert in six years.

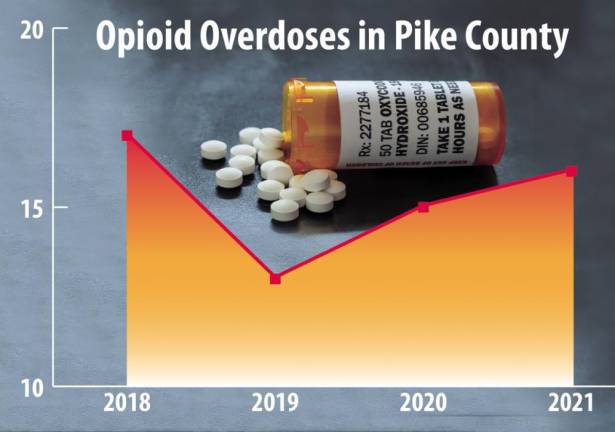

In Orange County, N.Y., overdoses jumped by 25 percent from 2019 to 2020, mirroring a grim trend nationwide. In Sussex County, N.J., overdoses increased by 17 percent. Pike County, Pa., saw a rise of 15 percent, and Passaic County, N.J., 8 percent.

The DEA says counterfeit pills are “mass-produced by criminal drug networks in labs, deceptively marketed as legitimate prescription pills, and are killing unsuspecting Americans at an unprecedented rate.”

The Centers for Disease Control says fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

And the number of people turning to drugs as a way to cope with the isolation and disruptions of the pandemic, now in its third year, is growing.

“We’re still in the midst of an epidemic, but I have to say that the Covid pandemic has kind of exacerbated things a little bit,” said Nicholas Loizzi, the alcohol and drug abuse director at the Sussex County Department of Health and Human Services.

The mental health issues caused by the pandemic can be especially tough for those with an addiction problem. “A lot of people have found themselves back to that road of addiction,” Loizzi said.

The CDC also cites reduced access to drug treatment during the pandemic to explain the increase in overdoses.

“It’s like a great storm of the worst possible things,” said Loizzi.

Will this kill me?

Fentanyl is a highly potent and addictive pain reliever. Pharmaceutical fentanyl is approved for treating severe pain, typically advanced cancer pain.

Identifying drugs laced with fentanyl has become a real concern for people with addiction, even for users of recreational drugs like marijuana. In the United States, more than two-thirds of opioid overdose deaths involve fentanyl.

“Drug dealers and distributors are using fentanyl, not to try to kill people, but to give them the ultimate high,” said Loizzi. “But they’re not being careful in how much they put in, and it only takes a little bit to kill somebody.”

Fentanyl is often laced in other drugs, like cocaine or marijuana. Oftentimes, buyers and sellers don’t even know their supply has been contaminated.

“Another thing that people are doing right now are taking fentanyl, putting them in pill presses, dyeing them to make them look like an oxycontin, 30-milligram pill,” said Chris Sorrentino, case management supervisor at Carbon Monroe Pike Drug & Alcohol Commission. “So people think they’re getting oxycontin, but they’re getting fentanyl, and it’s definitely another thing contributing to overdose deaths.”

Testing for fetanyl

One way to know for sure is to use a fentanyl test kit — small strips of paper that can detect fentanyl in any batch of illicit drugs, whether pills, powder, or injectables. But there’s a catch.

“The problem is, which is a loophole we have to work around, is if you are found with one of these test kits, it’s actually a crime of possession of paraphernalia for drug use in New Jersey,” said Loizzi.

It’s not so much a problem in New York. Tammy Rhein, the director of chemical dependency services at the Department of Mental Health in Orange County, said the department hands out fentanyl test kits.

“We are handing out test kits at our outreach efforts,” Rhein said. “And the department and the state are supporting of that.”

That’s not the case in Pennsylvania, though.

“Fentanyl strips for some reason are not legal, and I honestly don’t know why,” said Sorrentino. “It’s something a lot of people have been lobbying for, at least in Pennsylvania. There’s no logic to it...these tests are going to save people’s lives.”

Reaching out to those who need help

Drug manufacturers paid millions of dollars in court settlements last year for their contribution to the opioid crisis. In July, Johnson & Johnson agreed to pay $240 million to New York State for its role in the epidemic and to forego the manufacture of opioids.

“These funds will not bring back loved ones lost to the opioid epidemic but will hopefully assist others in getting treatment that can save their lives,” said Orange County Executive Steven Neuhaus in a statement when announcing the county’s allotment.

Each of the tristate counties in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania have their own initiatives to combat the opioid crisis. In New Jersey, Operation Helping Hand provides substance abuse treatment as an alternative to immediate incarceration.

Back in November, members of the Passaic County Prosecutor’s Office Narcotics Task Force concluded Operation Helping Hand, and made 33 arrests. Each person was screened privately by a peer recovery specialist. Thirty-one of those arrested accepted substance-abuse treatment.

“Over the last several years, as an overdose coalition, we’ve been trying to find different ways to bring awareness and help people seek treatment,” Loizzi said.

“The biggest concern here is the increase that we’ve been seeing here is with the overdose deaths,” said Sorrentino. “I know Covid has played a role in that, but it just helps us realize we need to find more effective ways to reach the individual that needs help.”

The history behind opioids:

The Centers for Disease Control outlines three waves of the opioid crisis:

The first wave began in the 1990s, when pharmaceutical companies encouraged their own opioid medicines and prescriptions.

The second wave started in 2010, when heroin was reintroduced to the “market” for people who had been previously prescribed opioids.

The third wave began in 2013 with the introduction of synthetic opioids, beginning with fentanyl, and continues today.

As many as 500,000 Americans died of an opioid overdose from 1999-2019, including medical and illicit opioids.

Opioids is a term for a variety of pain-relieving drugs: medically prescribed drugs like morphine, or oxycodone; and illicit drugs like heroin, or methamphetamine. Generally, most opioid addictions start with a prescription from a doctor.

The rate of opioid prescriptions was relatively steady up until the 1980s, which is when the groundwork for the first wave of the opioid crisis started to take root. The United States’ perspective on chronic pain started to change, and states began to pass pain treatment acts that removed the threat of prosecution for physicians who treated their patients’ pain with controlled substances.

“In the 90s, pharmaceutical companies introduced these products to the market and they advertised them as less addictive opioid pain relief medications, when in fact, they were highly addictive,” said Nicholas Loizzi, the alcohol and drug abuse director at the Sussex County Department of Health and Human Services. “But these companies encouraged doctors to prescribe them, and didn’t place any limits on how much they should prescribe.”

Last month, a New York State jury found Teva Pharmaceuticals and a handful of their subsidiary companies guilty of perpetuating the opioid crisis. County and state lawyers argued that the company downplayed their drugs’ risks and used faulty marketing techniques. It was one of the first trials of its kind.

“Back then, it got to the point where after a while (doctors) started to see how addictive these drugs really were, so they dialed back the amount of prescriptions they had been giving out,” said Loizzi.

But that created an entirely new problem. “The people that were addicted to it, without having any sort of detox or treatment for their addiction, resorted to going to the streets to get their drugs,” he said. “And that’s where we are today.”