Tom Quick: First came the legend, then the propaganda

By Ginny Privitar

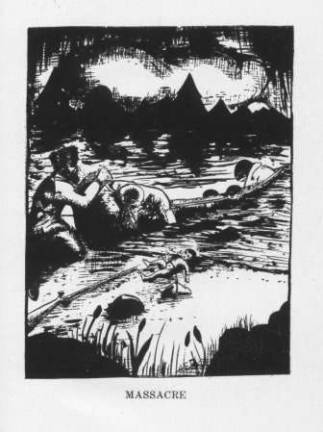

MILFORD — It's hard to tell fact from fiction in the case of Tom Quick. Known as “Avenger of the Delaware” and “Indian Slayer," he was famous — or infamous — for a massacre of native Americans in retribution for his father’s death at their hands. It's probable he killed some of them, but no hard documentation exists to say for sure. Much of his story is hearsay, the stuff of pulp fiction popular 50 years after his death. The tale was likely much embellished by Quick himself in an age when storytelling was entertainment.

Tom Quick Jr., born in 1734, was reputedly the first white child born in Milford. He lived through the horrors of the French the Indian Wars (1756-1763), a turning point in the lives of native Americans and settlers on what was then the frontier.

Tom Jr. was the youngest (or next to youngest) of 10 children born to Thomas Quick and Margriete Decker/Dekker. His father, Thomas Quick Sr., was orphaned as a boy and in 1702 started a seven-year apprenticeship to shipwright John King. The contract stated that Thomas be taught reading, writing, and math, and would receive a number of tools at the end of the seven years. His marriage to Margriete (Dekker/Decker) on Dec. 22, 1713, is recorded in Kingston, N.Y.

A promising beginning

At some point the Quicks left New York and lived for a while in Shippekonk, Sussex, in New Jersey. In 1733 Quick Sr. settled with his growing family in Milford, then known as Upper Smithfield. He built a log cabin, sawmill and grist mill on the banks of the Van De Mark creek. The following year, Tom Jr. was born.

Thomas Sr. is said to have been on friendly terms with the Lenni Lenape Indians for 20 years, even welcoming them in his home. Tom Jr. grew up with Lenni Lenape playmates and learned their language. Together they went hunting, fishing and exploring for miles around.

Over time, more white people came to the Delaware Valley, settling on native land. Tensions grew. The French and Indian War loomed. Both the French and the British used the Lenape as pawns, with most fighting on the side of the French. White settlers were caught in the middle, and there were atrocities on both sides.

The turning point

In the winter of 1756, Thomas Sr., Tom Jr., and another relative, and possibly a son-in-law of Thomas', Solomon Decker/Dekker, were near the river, foraging for hoop poles, when they were shot at by Indians. Thomas Sr. was hit. When his family tried to drag him to safety across the frozen river, Thomas Sr., mortally wounded, urged them to run for their lives. They did, and upon reaching safety saw to their horror the Indians overtake Thomas Sr. They scalped him and robbed him of silver buttons, or perhaps buckles, from his clothing. An Indian named Mus(k)wink, also known as Modeline, took part and later claimed to be the one who scalped him.

Tom Jr., 22 at the time, was traumatized. He vowed to kill as many Indians as he could: “To kill all, to spare none.” Over time, this loner, who never married, would do just that, roaming on both sides of the Delaware.

Tom’s exploits were mostly recounted by Tom himself. He claimed to have killed nearly 100 natives — men, women and children. He killed with a vengeance that to modern people seems pathological, but many believe the number he gave to be exaggerated. The white settlers considered Tom a hero, protecting them by eliminating a hostile enemy. Eventually, however, even some whites began to see Tom’s actions as excessive.

A different time, a different sensibility

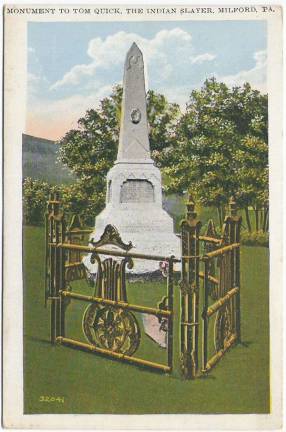

In August 1889, William Bross, a descendant of Tom’s brother Jacobus, erected The Settlers Monument (widely known as the Tom Quick monument) on Sarah Street in Milford. Bross was a former Milford resident, one-time principal of the Chester Academy in Chester, N.Y., and Lieutenant Governor of Illinois from 1865-69. Quick’s remains were transferred there from his burial place in Matamoras.

According to historian George Fluhr, the monument and the celebration that attended its dedication were more of a rallying symbol to support the troops that were still fighting Indians on the Western frontier. Tales of Quick’s deeds had for years fired the imaginations of volunteer would-be Indian fighters

In 1997 the monument was attacked by someone with a sledgehammer. It was rebuilt, but not re-erected, due to protests from some, including native American groups.

Why did Tom Quick commit his crimes? His niece and Bross’ ancestor, Maggie Quick, later recalled something Tom’s mother had said: the death of his father had turned his head.

In his old age, Tom went to live at the house of Jacobus Rosencranz/Rosencrance, in or near present-day Matamoras, where he died in 1796. He was buried on the farm of his friend in Rose Cemetery.