Tusten: Minisink's hero doctor

By Ginny Privitar Minisink Ford, N.Y. Col. Benjamin Tusten Jr. died in the calamitous Battle of Minisink, in Sullivan County, N.Y., on July 22, 1779. He led the militia that left Goshen, N.Y. to chase British forces up the Delaware River after their raid on Fort Decker and neighboring settlements, in present-day Port Jervis, N.Y.

The battle was a disaster for the Goshen militia. At least 48 militiamen were killed, while British forces, led by the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant, lost only seven men. Tusten, huddled under a rock shelter, cared for the wounded as best he could until he met his own end at the blow of a tomahawk.

A bulwark against smallpox Tusten was born on Dec. 11, 1743, in Southold, N.Y., and moved with his family to Goshen at a young age. He married Ann Brown in Newark, N.J. Together they had five children.

As a young man, Tusten was sent to Jamaica, on Long Island, to receive a classical education. He returned to Goshen at age 19 to study medicine under Dr. Thomas Wickham. He then spent a year with Dr. Burnet (or Barnet) of Newark, N.J., where he met his future wife. He finished his medical education under Dr. Thomas Jones, a noted New York City surgeon. In 1769 he returned to Goshen.

Tusten became known for his surgical skill and for introducing smallpox inoculations. He eventually inoculated 800 Orange County residents against this highly contagious and devastating disease, which killed up to half of those infected. Survivors were left severely scarred, blind, and infertile.

But Tusten's medical career, and his life, were cut short in the war for Independence.

Tusten's advice went unheeded Brant and his band conducted raids on New York's western frontier to draw part of Washingtons army away from the more important theater of war in the Hudson Valley. They burned farms from Oakland Valley to Port Jervis, then known as Peenpack, or Minisink. On July 20 they attacked a public event, possibly a funeral, at Minisink. A messenger raced to Goshen to alert the militia.

When Tusten and his men arrived at Minisink, they were joined by a small militia from Warwick, N.Y., under the command of Col. John Hathorn. Tusten and Hathorn advised the hastily assembled and ill-equipped militia to wait for reinforcements, but the men wanted to pursue Brant, who was now moving up the Delaware with captured horses, cattle, and prisoners. It is said that Major Samuel Meeker, from Sussex County, N.J., created unstoppable momentum when he mounted his horse, flourished his sword, and said, Let the brave men follow me! The cowards may stay behind.

They marched 17 miles and camped overnight near Minisink Ford. It is said that early on the morning of July 22, a shot was fired accidently, giving away the militia position. Brant soon cut off one militia unit of about 50 members from two other militia. Hathorn was forced to retreat, leaving Tusten and the Goshen militia hemmed in on a rocky hill. Near the end of an exhausting day of fighting, Brant's forces breached the line Tusten's men were defending at the top of the hill and outflanked the militia.

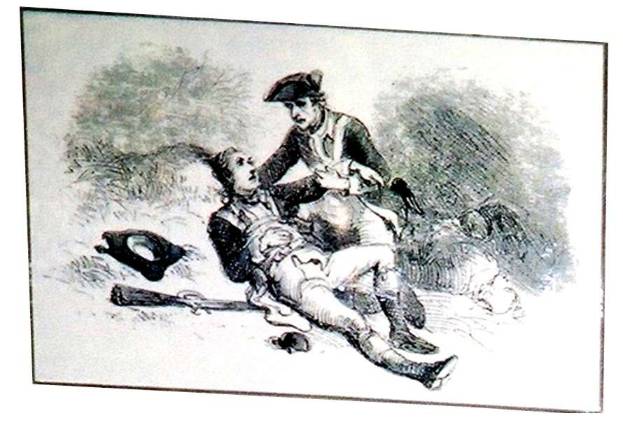

Tusten is said to have been wounded early in the battle. He spent his last hours tending the other wounded at the landmark known as Hospital Rock, which can be visited today at the Minisink Battleground Park in the Town of Highland, Sullivan County. The neighboring town to the north of Highland was named after the heroic doctor.

Because the untamed frontier was difficult to travel, the families of the slain could not immediately recover the bodies. It was not until 1822 that the bones were collected and buried in Goshen's Church Park, marked by a stone monument inscribed with the names of the dead. It is not known if Tusten's remains are interred there.

A crowd estimated at 15,000 witnessed the interment. General Hathorn, at age 80, placed into the grave two walnut caskets holding the gathered bones. In 1861 the original monument was replaced by the ornate obelisk that stands today opposite the 1841 Courthouse. The original monument was put on permanent display at the county government center.

Tustens home, on land originally belonging to the Denn family, and later by the Price family, was featured in "Old Orange Houses," Vol. II, by Mildred Parker Seese, in the article An early campaigner against smallpox. The house stood for many years on the Sarah Wells Trail, near the Otterkill (past Kipp Road), until it was torn down to make way for several mansions.